Looking Back at AI-Cademy and Looking Ahead to Re-University

Last year, I attended the AI-Cademy conference hosted by Higher Education Strategy Associates with a mix of excitement and curiosity that probably felt familiar to many people in the room.

We were deep in the hype cycle. Institutions were experimenting, vendors were showcasing prototypes, and campus leaders were asking big questions about what AI might mean for teaching, learning, planning, and administration. There was genuine energy, and also a fair amount of uncertainty.

After the conference, I wrote a blog post summarizing my top takeaways:

1️⃣ AI Can Be a Unifying Force in Higher Education

2️⃣ AI Literacy is a Real Concern for Senior Leadership

3️⃣ Building AI Capacity is No Small Task

4️⃣ AI for University Administration is Still in Its Infancy

5️⃣ AI is Reshaping Traditional Teaching

Reading it again now, what strikes me most is how much of that conversation was framed around possibility and capacity to get there. What could AI do? Where might this go? How quickly should institutions move? How do we give our team space to learn?

A year later, the conversation feels different. The idea of AI is still somewhat new, but has advanced considerably in this time. We see the rise of agentic AI, and a more thoughtful approach for where it should, and should not, be deployed.

My “Aha” Moment

One of the most memorable moments for me last year came not from a technical session, but from a keynote presentation by Arizona State University.

They described how AI was being used to support faculty members directly: drafting and refining learning outcomes, reviewing course syllabi, suggesting learning activities, and helping tailor instruction to different student needs. This wasn’t about automating teaching or replacing instructors. It was about reducing friction and making it easier for faculty to focus on pedagogy rather than paperwork.

As an adjunct faculty member myself, that's important. I always want to give my students the best resources I can muster, but often the constraint is my own time capacity to do so.

What surprised me even more were the conversations that followed. I spoke with faculty from disciplines I wouldn’t have expected to be early adopters - philosophy, as one example - who were already experimenting with AI in their teaching and research. Their core ideas were all about scaling their individual expertise so more students could benefit using learning techniques that worked well for them.

In the intervening year, institutions, faculty members, and students have all learned where AI can assist and where it isn't ideal. We've collectively learned that this technology is advancing so fast that what we knew yesterday could change tomorrow. But it's likely here to stay, so we should figure out how we leverage it and where we don't.

Less Hype, Thankfully

Fast forward to today, and some of the initial hype around AI has cooled - which I think many of us are grateful for.

What’s replacing it is more tangible: clearer use cases, better alignment with policies, and a stronger focus on outcomes.

At the same time, the broader context for Canadian higher education has shifted dramatically.

We are now two years out from major changes to Canada’s International Student Program. Study permits have declined sharply, by some estimates 60% below the targets. Many institutions are undershooting new targets. Across the sector, we’ve seen hundreds of program closures, thousands of layoffs, and billions of dollars in lost revenue. In my view, these impacts will be felt for at least 5 years before we find a new normal.

But there is another side to this story.

In the last year, I’ve also seen meaningful innovation emerge: new partnerships between institutions, deeper collaboration with industry, and renewed attention to learner pathways and workforce alignment. In some cases, constraints have forced institutions to rethink long-standing assumptions for how courses are delivered, what programs are offered, and how decisions get made.

If nothing else, the moment has made one thing very clear: intuition alone isn’t enough anymore.

Why Data and Decision-Making Matter Now

This brings us to next week’s Re-University conference in Ottawa, also hosted by Higher Education Strategy Associates.

At the conference, we’re hosting a roundtable session titled:

It’s a deliberately open-ended question.

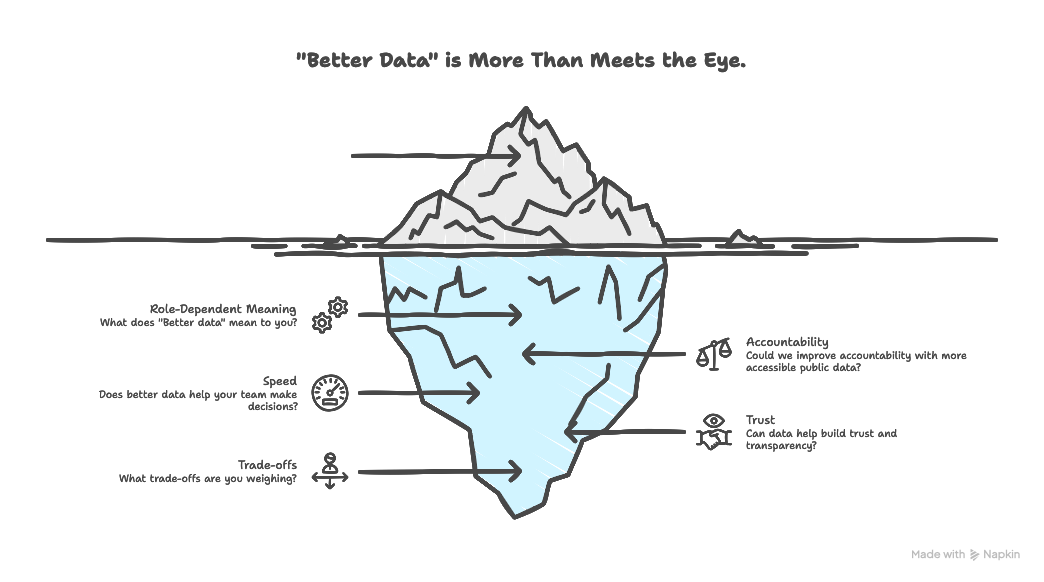

Not because the answers are vague, but because “better data” means different things depending on your role. For some, it’s about accountability. For others, it’s about speed. For others still, it’s about trust, transparency, or the ability to weigh real trade-offs rather than fight over whose spreadsheet is correct.

In the roundtable, we expect to explore questions like:

- Where does data meaningfully improve decision-making — and where does it not?

- How should institutions think about accountability when goals are shifting and resources are constrained?

- What trade-offs become visible when data is shared more openly?

- And perhaps most importantly: what does “better data” actually look like in practice?

These aren’t abstract questions anymore. They show up in budget meetings, program reviews, hiring decisions, and conversations with students every day.

Looking Ahead

Looking back on last year’s AI-Cademy, what stands out was institutions beginning to imagine new ways of working despite the challenging environment, by using data, technology, and good-old collaboration.

I’m looking forward to continuing that conversation in Ottawa, and to learning from how others are navigating this moment.

If you’ll be at Re-University, I hope you’ll join us. And whether or not you’re in the room, I’d love to hear your answer to the question:

If your institution had better data, what problem would you finally be able to solve?

Want to connect with Plaid while we're in Ottawa? Use the contact form to let us know!